What is Systems Thinking and How Can I Use it Today?

Systems thinking is a powerful mindset for understanding the world not as a series of isolated events, but as an interconnected web of relationships and influences. It invites us to see complexity clearly, to grasp how seemingly unrelated parts can work together, and to identify how small changes might have big consequences. In a time when the challenges we face are increasingly intricate, systems thinking offers a practical and compassionate approach to solving problems, managing uncertainty, and making sense of the chaos around us.

Although systems thinking has its roots in fields like ecology, engineering, and cybernetics, its applications go far beyond academia. Whether you are managing a team, trying to improve your morning routine, or navigating large-scale organizational change, the ability to see systems can help you move from reacting to symptoms to influencing causes. This post will help you understand what systems thinking really is, why it matters now more than ever, and how you can start using it today in both small and significant ways.

Understanding the Basics of Systems Thinking

Most of us are taught to think in straight lines. If something goes wrong, we look for a direct cause. If something works, we try to repeat the last step. This kind of linear thinking is useful for simple, well-defined problems, like following a recipe or fixing a broken hinge. But many of the problems we face in life and work are not that straightforward.

Systems thinking asks you to zoom out. Instead of just looking at individual parts, you examine how those parts interact over time. For example, imagine a workplace where burnout is increasing. A linear thinker might blame individuals for poor time management or lack of motivation. A systems thinker, on the other hand, would look at the incentives, communication patterns, team structures, leadership expectations, and feedback loops that might be reinforcing that burnout. They would ask questions like: How does our reward system shape behavior? What signals are people getting about performance and rest? What unspoken norms are circulating across the organization?

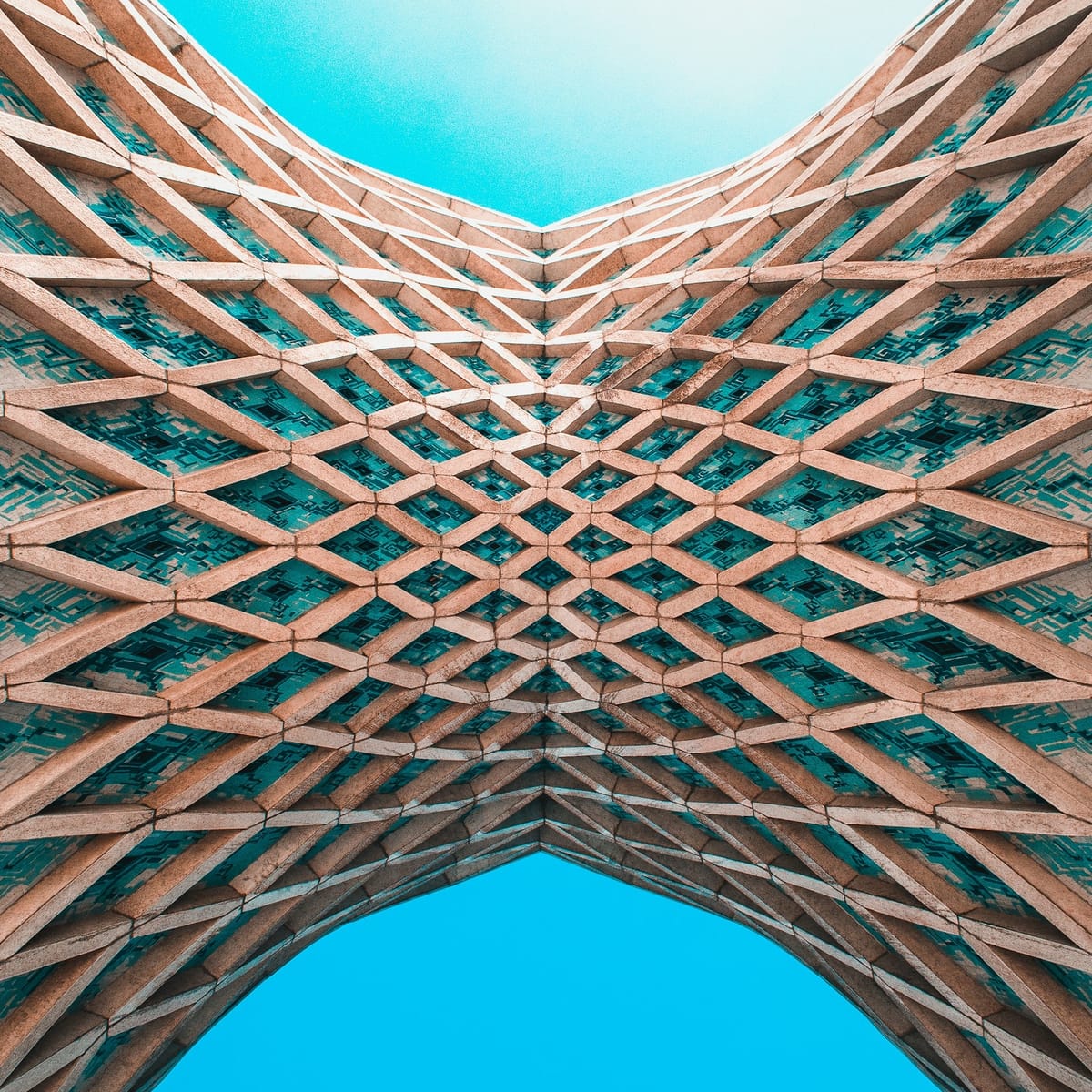

At its most fundamental level, a “system” is a collection of elements that are interconnected in such a way that they produce a pattern or behavior over time. These elements might include people, tools, resources, processes, and values. But what makes a system a system is not just its parts, but how those parts interact. These interactions often produce behaviors that are different from what any one part would do on its own.

Understanding this distinction helps explain why solving a problem in one area can lead to issues in another. You cannot change one part of a system without affecting the rest. And often, the outcomes we see are not caused by individual choices but by the structure of the system itself.

The Power of Feedback Loops

Feedback loops are essential to understanding how systems behave. A feedback loop occurs when part of a system’s output is routed back into the system as input. This feedback can either reinforce a pattern or balance it out. Recognizing and mapping feedback loops helps you identify why certain outcomes keep happening, even when people are trying hard to change them.

A reinforcing feedback loop amplifies change in one direction. The more it happens, the more it continues to happen. A classic example is the growth of social media platforms. As more people join a network like Instagram, the platform becomes more valuable for everyone, which attracts even more users. The more popular it becomes, the faster it grows. This is a self-reinforcing loop. In business, reinforcing loops can be seen in brand reputation. The better your reputation, the more customers you attract, which leads to more visibility and more reputation-building moments.

Balancing feedback loops work differently. They try to stabilize the system by pushing back against change. Think of your body’s temperature regulation system. If you get too hot, you sweat. If you get too cold, you shiver. These mechanisms are not random—they exist to maintain equilibrium. In organizations, balancing loops can show up when growth begins to strain internal capacity. For example, as a company expands quickly, quality may begin to drop. Customers complain, and leadership slows down expansion to improve the product. That is a balancing feedback in action.

Importantly, these loops often interact. A reinforcing loop might dominate until a balancing loop kicks in. That is why exponential growth in a company can suddenly plateau, or why an initial surge of motivation in a new habit fades over time. Understanding which loops are active, and how they relate to one another, gives you a way to shift patterns rather than just symptoms.

Why Systems Thinking Matters Right Now

We live in a time of interdependence. The world is more connected than it has ever been, and while that brings incredible opportunities, it also brings complexity. Challenges such as climate change, economic inequality, mental health crises, organizational dysfunction, and social polarization are not linear problems. They do not have clear causes or quick fixes. They are influenced by countless variables, feedback loops, and histories of decision-making that span across domains and time.

Systems thinking is uniquely suited to help us navigate these challenges. It encourages humility and curiosity. Instead of jumping to conclusions, it invites us to understand the broader context. When we approach problems systemically, we begin to see not only what is happening, but why—and what might happen next if we intervene carelessly or thoughtfully.

In business, systems thinking can help leaders avoid the pitfalls of short-term fixes that create long-term problems. For example, a company might cut costs by laying off employees, only to find that morale drops, productivity falters, and turnover increases. Systems thinking would suggest examining how cost structures, culture, communication, and workload are interrelated—and where a smarter intervention could produce more sustainable outcomes.

In education, systems thinking can shed light on why test scores or graduation rates remain low despite repeated reform efforts. It asks us to examine social supports, community involvement, curriculum design, policy incentives, and even nutritional access. In public health, it can help us understand how housing, transportation, and systemic inequities influence disease outcomes and recovery rates. Across every field, systems thinking equips us to deal with complexity rather than pretend it does not exist.

Using Systems Thinking at Work and in Daily Life

One of the great misconceptions about systems thinking is that it is only useful for large-scale analysis or policy design. In reality, it is a mindset that can dramatically improve how you think, plan, and act in everyday situations.

Start by thinking relationally instead of linearly. For example, if your team is consistently missing deadlines, resist the urge to blame individuals. Instead, ask what systemic factors might be at play. Are goals unclear? Is there a hidden incentive to start new projects instead of finishing old ones? Is the feedback process slow or ambiguous? Thinking this way helps you uncover the actual root causes of the problem and prevents you from treating symptoms as if they were causes.

Next, pay attention to patterns over time. If a problem keeps resurfacing despite efforts to fix it, that is a strong clue that you are dealing with a systemic issue. Start documenting when it happens, who is involved, what else is going on at the time, and how the organization or group responds. Over time, you will begin to see patterns that help you predict and prevent future issues, not just react to them.

Look for delayed consequences. Systems often have lag times between cause and effect, which can make it hard to connect decisions with their outcomes. You might implement a new policy today that causes confusion or disengagement three months from now. By anticipating these delays, you can build better communication plans, set more realistic expectations, and measure the right leading indicators.

Finally, shift your focus from blame to design. If something is not working, ask how the system might be encouraging or enabling that behavior. Are there mixed messages? Misaligned rewards? Gaps in visibility or authority? If so, redesigning the system can create better results without needing to rely on personal heroics.

Systems Thinking and Personal Growth

Systems thinking is not just a professional tool. It can also help you understand your own habits, decisions, and emotional patterns in a deeper and more constructive way. Your life is filled with systems—your routines, your relationships, your information diet, your thought loops—and they are constantly influencing your behavior and mood.

Take habits, for instance. If you are trying to break a habit like checking your phone compulsively, systems thinking encourages you to look beyond willpower. What are the triggers? What is the reward loop? What environmental cues support the habit? Are you using your phone as a form of stress relief, procrastination, or social connection? By redesigning your environment or changing the conditions that lead to the habit, you can alter the system instead of fighting it every day.

In relationships, systems thinking can help you shift from blame to mutual insight. If you and a partner or colleague keep having the same argument, there is likely a feedback loop in play. One person reacts, the other responds, and the pattern repeats. Naming that dynamic as a system creates space to reflect together and shift how you engage with each other. It becomes less about who is right and more about what system you are co-creating.

Even your energy and focus are systemic. Your sleep, nutrition, screen time, and social interactions all shape how alert and effective you feel. Trying to “be more productive” without adjusting those surrounding systems is like trying to drive faster without checking the tires or fuel. Once you start viewing personal well-being through a systems lens, you stop trying to optimize every task and start building conditions where better outcomes happen naturally.

Getting Started with a Systems Thinking Practice

You do not need a complex toolkit to begin thinking systemically. All you need is the willingness to ask better questions and the patience to sit with complexity. Start with small, consistent practices.

When facing a persistent problem, draw a simple diagram showing the elements involved and how they influence each other. These causal loop diagrams do not need to be perfect; their purpose is to help you surface hidden assumptions and see interconnections. Use arrows to show relationships and ask yourself: What reinforces this pattern? What balances it? Where is energy flowing in or out of the system?

In team settings, make it a norm to ask systemic questions. What’s changing around us that might be shaping this behavior? Are we solving the same problem repeatedly without addressing its roots? Are there incentives or policies we created for one purpose that are now having unintended effects?

Also, cultivate an awareness of your own role in the systems you participate in. Systems thinking is not just about fixing others. It is also about reflecting on how our actions and attitudes reinforce or disrupt the patterns we are part of.

Finally, learn to tolerate ambiguity. Systems thinking rarely offers clear-cut answers. But it gives you a richer map, one that respects complexity and prepares you to act with more wisdom, less haste, and deeper insight.

A More Generous Way of Thinking

Systems thinking is not a magic wand, nor is it a rigid framework. It is a way of seeing the world with more clarity, compassion, and creativity. It helps us move from blame to understanding, from reactivity to design, and from short-term wins to long-term change.

When you think in systems, you stop treating symptoms as problems. You start identifying leverage points. You become someone who sees the bigger picture without losing sight of the people in it.

And that makes systems thinking not just a tool for work or policy—but a mindset for life.