What Is Aesthetics? The Philosophy of Beauty and Art

Aesthetics is more than art theory. It’s how we make sense of beauty, taste, and the feelings that art awakens in us.

Why does a piece of music give you chills? Why do people argue over abstract paintings or obsess over the perfect photograph of their morning coffee? These moments seem small, but they tap into something profound. Beneath every gasp at a sunset or debate over a film’s merit lies a deep, often invisible current of thought—one that has occupied philosophers for over two thousand years. That current is aesthetics, the branch of philosophy devoted to beauty, taste, and the strange, stirring power of art.

Aesthetics is not simply the study of what looks good or feels meaningful. It’s a way of asking why certain things captivate us and what that says about our minds, our cultures, and our values. It sits at the crossroads of emotion and intellect, pulling from psychology, ethics, metaphysics, and even politics. From Plato’s suspicion of art to Kant’s search for universal beauty to today’s tangled debates over taste and technology, aesthetics offers a way to understand not only art, but ourselves.

Plato, Imitation, and Ideal Forms

The origins of Western aesthetic theory trace back to Plato, who famously distrusted art. In his Republic, Plato characterized art as mere imitation—twice removed from truth. A painting of a chair, for example, imitates the physical chair, which itself is only a shadow of the ideal “Form” of Chairness. In this schema, the artist was not a creator but a copier, misleading the audience with illusions.

This skeptical view of aesthetics was rooted in Plato’s metaphysics. Since true reality lay in the realm of Forms—eternal, unchanging ideals—any sensory or emotional response to art was seen as a distraction from rational truth. Plato’s student Aristotle would later challenge this view, but Plato’s basic framing of art as imitation (mimesis) became a lasting conceptual foundation in aesthetics.

Aristotle and Catharsis

Unlike his mentor, Aristotle saw art—particularly drama—as not only valuable but essential to emotional life. In Poetics, Aristotle argued that tragedy functions to evoke and then purge emotions like pity and fear through a process he called catharsis. Art does not merely copy life; it organizes and intensifies it, revealing universal truths through particular stories.

This was a major shift. For Aristotle, art was a way of making sense of the human experience, not a distraction from it. He moved aesthetics away from rigid metaphysical frameworks and toward a more empirical, experience-based understanding. His influence can be seen in later thinkers who connect the power of art with emotion, ethics, and narrative form.

The Enlightenment and the Rise of Subjectivity

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as Enlightenment ideas about reason, individual rights, and empirical knowledge took hold, aesthetics underwent a transformation. Thinkers like David Hume and Immanuel Kant began to explore taste and beauty not just as metaphysical or moral issues, but as problems of perception, judgment, and universality.

David Hume, in his essay “Of the Standard of Taste,” argued that beauty is not inherent in objects but resides in the minds of those perceiving them. Yet he didn’t endorse pure relativism. Hume believed that good taste could be cultivated through experience, education, and exposure. The existence of “true critics,” he claimed, helped anchor aesthetic judgment, even in the face of subjective variation.

Immanuel Kant took this further in his Critique of Judgment, where he sought to explain how judgments of beauty could be both subjective and universal. Kant believed that when we find something beautiful, we experience a “free play” between imagination and understanding. Though the judgment is subjective—it comes from the individual—it also claims universality. When you say “This sunset is beautiful,” you’re not just describing your own reaction; you’re implicitly saying that everyone ought to find it beautiful.

This move toward subjectivity did not mean that beauty was arbitrary. Rather, Kant’s approach highlighted the unique way aesthetic experience straddles personal feeling and shared human perception. His theory laid the groundwork for much of modern aesthetics and remains foundational in contemporary debates.

Romanticism and the Sublime

The nineteenth century brought another shift with the rise of Romanticism, which prized emotion, nature, and individual expression. Philosophers and poets of this era—like Friedrich Schiller, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and later Arthur Schopenhauer—began to emphasize the role of aesthetic experience as transcendent and even redemptive.

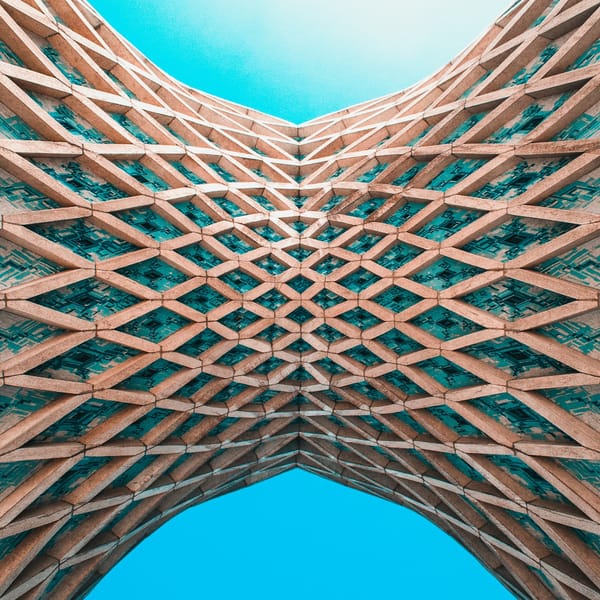

Central to Romantic aesthetics was the concept of the sublime—a feeling of awe, even terror, in the face of vastness, power, or mystery. Edmund Burke and later Kant wrote about the sublime as distinct from beauty. While beauty calms and pleases, the sublime overwhelms and elevates. A storm at sea or a mountain range might terrify, but in doing so, they also awaken a deeper sense of human potential and spiritual insight.

This era marked a turning point where art was not just decorative or entertaining. It was viewed as a powerful means of emotional and existential engagement. Aesthetics began to merge with broader questions of freedom, individuality, and metaphysical longing.

Modernism, Formalism, and the Avant-Garde

The twentieth century brought enormous upheaval to aesthetic theory. As artists broke away from classical forms and traditions, philosophers struggled to keep pace. What counted as art? Could a urinal signed “R. Mutt” (Marcel Duchamp’s infamous Fountain) really be considered a meaningful aesthetic object?

Thinkers like Clive Bell and Clement Greenberg argued for formalism—the idea that art should be judged by its visual form, not by its subject matter or emotional effect. According to this view, a painting is valuable because of its composition, color, and line—not because it tells a story or evokes a feeling.

This led to fierce debates about the role of intention, audience, and context. Ludwig Wittgenstein, in his later work, took a more language-based approach, suggesting that the meaning of “art” arises from its use in different social contexts. Meanwhile, Theodor Adorno critiqued mass culture and commodification, arguing that true aesthetic experience resists easy consumption and challenges the viewer to think critically.

Contemporary Aesthetics and Everyday Life

Today, aesthetics is no longer confined to museums or galleries. Philosophers like Nelson Goodman, Arthur Danto, and more recently, Yuriko Saito have argued that aesthetic experience permeates everyday life—from the design of a toothbrush to the layout of a city street. Questions of taste, style, and beauty now intersect with politics, identity, and technology.

Feminist and postcolonial theorists have expanded the field by questioning whose aesthetics have been historically privileged and why. For instance, bell hooks wrote about “aesthetic inheritance” as both a site of empowerment and exclusion. Aesthetic judgment, once seen as a neutral exercise in taste, is now understood to carry the weight of culture, power, and ideology.

Digital media has also changed the terrain. Algorithms shape what we see and hear. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Spotify filter aesthetic choices through popularity metrics and advertising goals. The experience of beauty and art, once private or communal, is now globalized and optimized.

Still, the fundamental questions remain. Why does a poem bring you to tears? Why does a piece of music linger in your mind long after it ends? Why do people care so deeply about whether something is art—or isn’t?

These are not trivial questions. They go to the heart of what it means to feel, to interpret, to judge, and to be human.