The Truth The Color of Law Forces Us to Confront

Reading The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein is a gut-punch. It’s not that I didn’t know segregation was intentional, but seeing the extent to which the government actively created and enforced it—and how deeply those policies still shape our society today—is infuriating. This wasn’t about private prejudice or market forces. It was the law. It was policy. And worst of all, despite some of these laws being repealed, their effects have never been truly addressed or undone.

For years, we’ve been told a convenient lie—that racial segregation in housing was the result of individual choices, economic class differences, or just some unfortunate but organic social trend. But as Rothstein lays out in devastating detail, “Today’s residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States.” The government didn’t just allow segregation to happen; it engineered it.

Public Housing and the Creation of Black Ghettos

One of the most enraging examples is how public housing was used to increase segregation, not alleviate it. Instead of providing mixed-income housing that could have led to integration, local and federal governments designed public housing to concentrate Black families in urban ghettos. Rothstein points out that “the purposeful use of public housing by federal and local governments to herd African Americans into urban ghettos had as big an influence as any in the creation of our de jure system of segregation.”

Even after the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional in schools, the government refused to apply the same logic to housing. Berchmans Fitzpatrick, general counsel of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, stated that Brown “did not apply to housing.” In 1955, the Eisenhower administration even formally abolished a policy—one that was never actually enforced—that would have required Black and white public housing to be of equal quality. Instead, public housing authorities were allowed to give priority to white applicants, while Black families were often placed on long waiting lists. Even worse, urban renewal projects meant that Black neighborhoods were frequently demolished, displacing thousands of families without providing them adequate replacement housing.

Redlining, Racial Zoning, and Exclusionary Practices

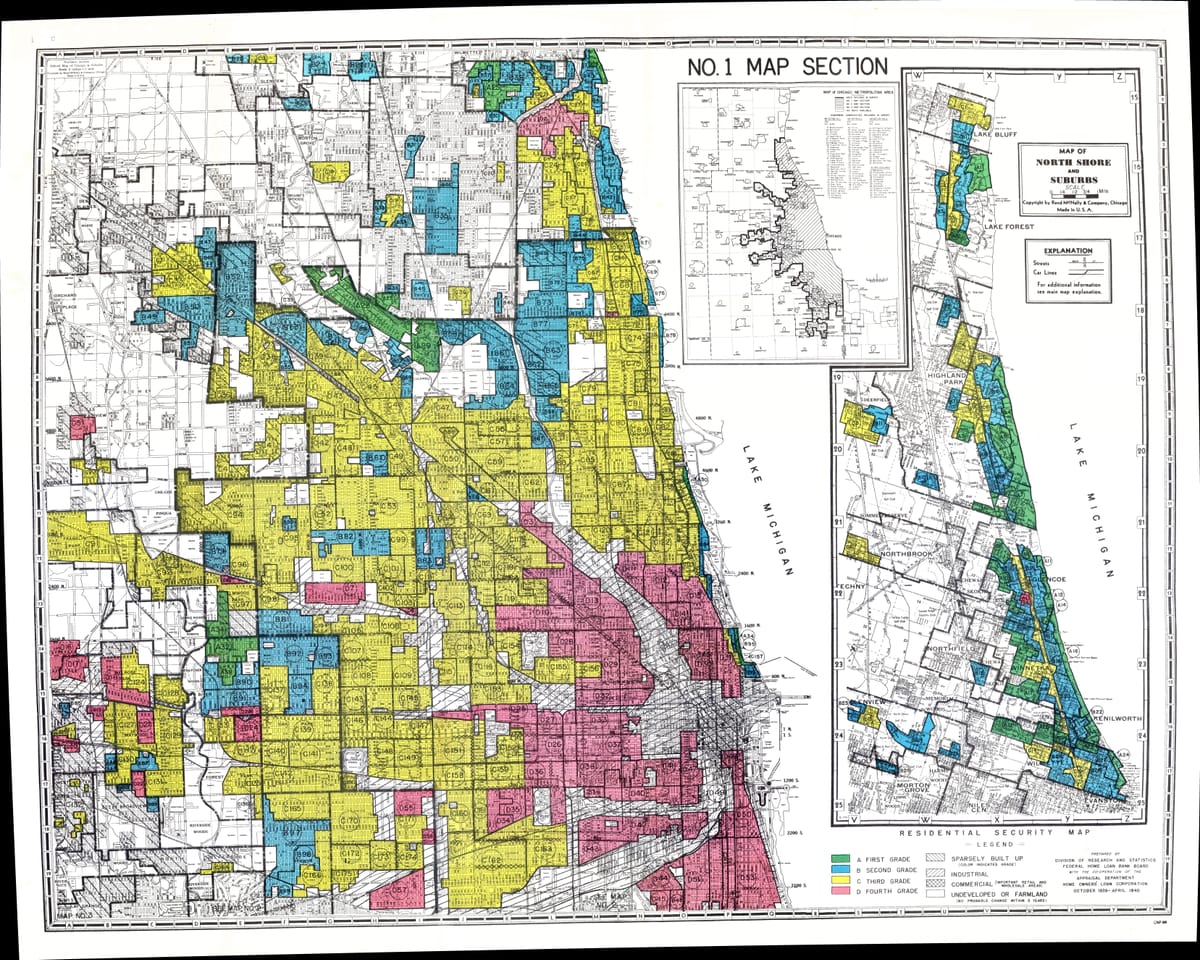

The racism in federal housing policy didn’t stop at public housing. Private homeownership—one of the primary ways families build generational wealth—was systematically closed off to Black Americans. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which revolutionized mortgage lending in the mid-20th century, refused to insure loans in neighborhoods where Black people lived. This is where redlining comes in: maps were drawn to literally mark Black areas as “high-risk,” ensuring banks wouldn’t lend there.

But it wasn’t just the financial industry acting on its own. The government required racial segregation in the neighborhoods it backed. The FHA’s appraisal standards “included a whites-only requirement,” meaning it would only insure mortgages in segregated communities. The FHA even went so far as to encourage physical separation, stating that “[n]atural or artificially established barriers will prove effective in protecting a neighborhood and the locations within it from adverse influences, includ[ing] prevention of the infiltration of… lower class occupancy, and inharmonious racial groups.”

And then there were exclusionary zoning laws, which ensured that Black families—especially those who were low-income—were kept out of middle-class white suburbs. As Rothstein puts it, “Exclusionary zoning ordinances could be, and have been, successful in keeping low-income African Americans, indeed all low-income families, out of middle-class neighborhoods.” Even when explicit racial zoning was ruled unconstitutional, cities got around it by instituting zoning laws that banned apartments or required large, single-family lots—effectively keeping Black families out of wealthier areas.

The Lies of White Flight

Another infuriating myth that Rothstein dismantles is the idea that property values plummeted when Black families moved into white neighborhoods. This was a deliberate lie spread by the real estate industry and the FHA itself. In reality, “statistical evidence contradicted the FHA’s assumption that the presence of African Americans caused the property values of whites to fall. Often racial integration caused property values to increase.”

But that didn’t stop real estate speculators from manipulating the market with a tactic called blockbusting. As Rothstein describes it, blockbusters “bought properties in borderline black-white areas; rented or sold them to African American families at above-market prices; persuaded white families residing in these areas that their neighborhoods were turning into African American slums and that values would soon fall precipitously; and then purchased the panicked whites’ homes for less than their worth.” These unethical practices reinforced the myth that Black residents were a threat to property values, when in reality, the decline was artificially created.

Acknowledgment Isn’t Enough—We Need Reparative Action

What makes all of this even more frustrating is that, while some of these policies have been repealed, their damage has never been repaired. The wealth gap between Black and white Americans exists because Black families were systematically excluded from the benefits of homeownership and wealth accumulation. Rothstein makes it clear that “we have created a caste system in this country, with African Americans kept exploited and geographically separate by racially explicit government policies. Although most of these policies are now off the books, they have never been remedied and their effects endure.”

And yet, when the idea of actually fixing this injustice comes up, people act like it’s impossible. Rothstein acknowledges that there’s no simple fix, writing that “remedies that can undo nearly a century of de jure residential segregation will have to be both complex and imprecise.” But that doesn’t mean we get to throw up our hands and say it’s too hard. We need economic policies that directly address the disparities created by housing segregation—full employment policies, minimum wage increases, and transportation infrastructure to connect workers with better jobs. More than that, we need real investment in integrating housing.

But none of that will happen as long as people keep buying into the myth that segregation just “happened.” Rothstein warns that “remedies are inconceivable as long as citizens, whatever their political views, continue to accept the myth of de facto segregation.” If we don’t acknowledge that segregation was intentionally created by law, we won’t demand that it be undone by law.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Rothstein makes one last point that should make us all uncomfortable: “Under our constitutional system, government has not merely the option but the responsibility to resist racially discriminatory views, even when—especially when—a majority holds them.” That means the government has an obligation to correct the harm it caused—not just to apologize, not just to acknowledge, but to act.

Undoing de jure segregation will be hard. It will take resources, political will, and an honest reckoning with how we got here. But the first step is refusing to accept the convenient lie that segregation was ever accidental. The government built this system. The government must be the one to dismantle it.

And we should be furious that it hasn’t happened yet.